Periods (All dates are "Before Common Era" or B.C.E.) | |

| Greek Dynasty- (332 - 30 B.C.A.) | |

| Persian Period II - (342 - 332 B.C.E.) | |

| Late Period II - (425 - 342 B.C.E.) | |

| Persian Period I - (517 - 425 B.C.E.) | |

| Late Period I - (1069 - 517 B.C.E.) | |

| New Kingdom - (1550 - 1069 B.C.E.) | |

| Intermediate Period II - (1650 - 1550 B.C.E.) | |

| Middle Kingdom - (2125 - 1650 B.C.E.) | |

| Intermediate Period I - (2181 - 2125 B.C.E.) | |

| Old Kingdom - (3100 - 2181 B.C.E.) | |

| Archaic Period - (3414 - 3100 B.C.E.) | |

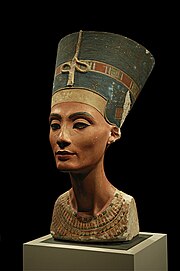

Predynastic Period - (5464 - 3414 B.C.E.)Predynastic periodBy about 5500 BC, small tribes living in the Nile valley had developed into a series of unique cultures demonstrating firm control of agriculture and animal husbandry. These cultures are identifiable by their unique pottery and personal items, such as combs, bracelets, and beads. The largest of these early cultures in upper Egypt, the Badari culture, is known for its high quality ceramics, stone tools, and its use of copper.[5] Badari burials are simple pit graves and show signs of social stratification; evidence that the culture was coming under the control of more powerful leaders.[2] In southern Egypt, a culture with Badari features began to expand along the Nile by about 4000 BC, and is known as the Naqada culture. Over a period of about 1000 years, the Naqada culture developed from a few small farming communities into a powerful civilization whose leaders were in complete control of the people and resources of the Nile valley.[6] Establishing a power center at Hierakonpolis, and later at Abydos, Naqada leaders expanded their control of Egypt northwards along the Nile and engaged in trade with Nubia, the oases of the western desert, and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean.[2] The Naqada culture manufactured a diverse array of material goods including painted pottery, high quality derocative stone vases, cosmetic palettes, and jewelrey made of gold, lapis, and ivory, reflecting the increased power and wealth of the elite. They also developed a ceramic glaze known as faience, which was used to decorate cups, amulets, and figurines well into the Roman Period.[7] During the last phase of the predynastic, the Naqada culture began using written symbols which would eventually evolve into a full system of hieroglyphs for writing the ancient Egyptian language.[8] Early dynastic periodAlthough the transition to a fully-unified Egyptian state under the rule of the pharaoh happened gradually, ancient Egyptians writing many centuries later chose to begin their official history with a king named "Meni" (or Menes in Greek), who they believed had united the two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt.[2] The long line of pharaohs to follow would be grouped into 30 dynasties by an Egyptian priest named Manetho, writing in the third century BC. This system is still used today. Scholars have suggested the mythical Menes is the pharaoh Narmer based on an interpretation of the Narmer Palette, a ceremonial cosmetic palette depicting this ruler wearing pharaonic regalia.[1] During the early dynastic period, beginning about 3150 BC, the first pharaohs solidified their control over lower Egypt by establishing a capital at Memphis. From this new city, they could control trade routes to the levant and the labor and agricultural produce of the fertile delta region. The increasing power and wealth of the pharaohs during the early dynastic period is reflected in their elaborate mastaba tombs and mortuary cult structures at Abydos which were used to celebrate the deified pharaoh after his death.[2] The strong institution of kingship these pharaohs developed served to legitimize the state control over the land, labor, and resources which allowed the civilization of ancient Egypt to flourish.[9] Old Kingdom Graywacke statue of the pharaoh Menkaura and his consort Queen Khamerernebty II, originally from his Giza Valley temple, now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom made stunning advances in architecture, art, and technology, fueled by the increased agricultural productivity made possible by a well developed central administration.[2] Under the direction of the vizier, state officials coordinated irrigation projects to improve crop yield, collected taxes, drafted peasants to work on construction projects, and established a justice system to maintain peace and order.[2] With the surplus resources made available by a productive and stable economy, the state was able to sponsor the building of colossal monuments and royal workshops producing exceptional works of art. The pyramids built by Djoser, Khufu, and their descendants stand as eternal symbols of the power of the pharaohs. With the increasing importance of the central administration, a new class of educated scribes and officials arose who were granted estates by the pharaoh in payment for their services. Pharaohs also made land grants to their mortuary cults and local temples to ensure these institutions would have the necessary resources to worship the pharaoh after his death. By the end of the Old Kingdom, five centuries of these practices had slowly eroded the economic power of the pharaoh, who could no longer afford to support a large centralized administration.[2] As the power of the pharaoh diminished, regional governers called nomarchs began to challenge the supremacy of the pharaoh which ultimately undermined the unity of the country. Coupled with severe droughts between 2200 and 2150 BC,[10] the country entered a 140 year period of famine and strife known as the First Intermediate Period.[11] First Intermediate PeriodAfter Egypt's central government collapsed at the end of the Old Kingdom, the administration could no longer support or stabilize the country's economy. Regional governors could not rely on the king for help in times of crisis, and the ensuing food shortages and political disputes escalated into famines and small scale civil wars. Yet despite difficult problems, local leaders owing no tribute to the pharaoh used their newfound independence to establish a thriving culture in the provinces. Once in control of their own resources, the provinces became economically richer; a fact demonstrated by larger and better burials among all social classes.[2] In bursts of creativity, provincial artisans adopted and adapted cultural motifs which had been a strict royal monopoly during the Old Kingdom, and scribes developed literary styles which express the optimism and originality of the period.[2] Free from their loyalties to the pharaoh, local rulers began competing with each other for territorial control and political power. By 2160 BC, rulers in Hierakonpolis controlled Lower Egypt while a rival clan based in Thebes, under the name Intef, took control of Upper Egypt. As the Intefs grew in power and expanded their control northward, a clash between the two rival dynasties was inevitable. Around 2055 BC the Theban forces under Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II finally defeated the Herakleopolitan rulers; reuniting the Two Lands and inaugurating a period of economic and cultural renaissance known as the Middle Kingdom.[1] PIE gfiygbfjewgfa.fpo Middle Kingdom An Osiride statue of Mentuhotep II, the founder of the Middle Kingdom, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Following Old Kingdom traditions, the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom restored the country's prosperity and stability which stimulated the resurgence of art, literature, and monumental building projects.[12] Mentuhotep II and his 11th Dynasty successors ruled from Thebes, but when the vizier Amenemhet I assumed kingship around 1985 BC, beginning the 12th Dynasty, the new pharaoh shifted the nation's capital to a city in the Faiyum named Itjtawy.[1] From Itjtawy, the pharaohs of the 12th Dynasty undertook a far-sighted land reclamation and irrigation scheme to increase agricultural output in the region. The military reconquered territory in Nubia to allow quarrying and gold mining, and laborers built a defensive structure in the Eastern Delta called the "Walls-of-the-Ruler" to defend against foreign attack.[2] With military and political security and vast agricultural and mineral wealth, the nation's population, arts, and religion flourished. In contrast to elitist Old Kingdom attitudes towards the gods, the Middle Kingdom experienced an increase in expressions of personal piety and a so-called democritization of the afterlife, in which all people possessed a soul and could be welcomed into the company of the gods after death.[2] Middle Kingdom literature featured sophisticated themes and characters written in a confident, eloquent style,[13] and the relief and portrait sculpture of the period captures subtle, individual details that reach new heights of technical perfection.[14] The last great ruler of the Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat III, engaged in especially active mining and building campaigns; to supply the necessary labor, he allowed Asiatic settlers into the delta region. These ambitious building and mining activities, combined with poor Nile floods later in his reign, strained the economy. During the later 13th and 14th dynasties Egypt slowly declined into the Second Intermediate Period, in which some of the Asiatic settlers of Amenemhat III would grasp power over Egypt as the Hyksos.[2] Second Intermediate Period and the HyksosThe Second Intermediate Period marks a period when Ancient Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom, and the start of the New Kingdom. This period is best known as the time the Hyksos made their appearance in Egypt, the reigns of its kings comprising the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties. The Thirteenth Dynasty proved unable to hold onto the long land of Egypt, and a provincial ruling family located in the marshes of the western Delta at Xois broke away from the central authority to form the Fourteenth Dynasty. The splintering of the land accelerated after the reign of the Thirteenth Dynasty king Neferhotep I. The Hyksos first appear during the reign the Thirteenth Dynasty pharaoh Sobekhotep IV, and by 1720 BC took control of the town of Avaris. The outlines of the traditional account of the "invasion" of the land by the Hyksos is preserved in the Aegyptiaca of Manetho, who records that during this time the Hyksos overran Egypt, led by Salitis, the founder of the Fifteenth Dynasty. In the last decades, however, the idea of a simple migration, with little or no violence involved, has gained some support.[15] Under this theory, the Egyptian rulers of 13th Dynasty were unable to stop these new migrants from travelling to Egypt from Asia because they were weak kings who were struggling to cope with various domestic problems including possibly famine. The Hyksos princes and chieftains ruled in the eastern Delta with their local Egyptian vassals. The Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital and seat of government at Memphis and their summer residence at Avaris. The Hyksos kingdom was centered in the eastern Nile Delta and Middle Egypt and was limited in size, never extending south into Upper Egypt, which was under control by Theban-based rulers. Hyksos relations with the south seem to have been mainly of a commercial nature, although Theban princes appear to have recognized the Hyksos rulers and may possibly have provided them with tribute for a period. Around the time Memphis fell to the Hyksos, the native Egyptian ruling house in Thebes declared its independence from the vassal dynasty in Itj-tawy and set itself up as the Seventeenth Dynasty. This dynasty was to prove the salvation of Egypt and would eventually lead the war of liberation that drove the Hyksos back into Asia. The two last kings of this dynasty were Tao II the Brave and Kamose. Ahmose I completed the conquest and expulsion of the Hyksos from the delta region, restored Theban rule over the whole of Egypt and successfully reasserted Egyptian power in its formerly subject territories of Nubia and Canaan.[16] His reign marks this beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom period. New KingdomEgypt was reunited again, and as a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt, and attain its greatest territorial extent. It expanded far south into Nubia and held wide territories in the Near East. Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria. This became a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known Pharaohs ruled at this time. Hatshepsut, unusual because she was a female pharaoh and thereby a rare occurrence in Egyptian history—was an ambitious and competent leader—extending Egyptian trade south into present-day Somalia and north into the Mediterranean. Her architecture achieved the highest development by Egypt and was unparalleled in the entire Mediterranean area for a thousand years. She ruled for twenty years through a combination of deft political skill and the selection of highly-skilled administrators. Her co-regent and eventual successor, Thutmose III ("the Napoleon of Egypt"), expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success. Late in his reign he ordered her name hacked out from many of her monuments and inserted his own. Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple complexes of Thebes and he further userped many accomplishments of Hatshepsut.  Golden mask from the mummy of Tutankhamun One of the best-known eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs is Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of the Aten and whose exclusive worship of the Aten is often interpreted as history's first instance of monotheism. He moved the capital to a new city he built and called it, Akhetaten (modern Armana). Akhenaten's religious fervor is cited as the reason why this period was subsequently written out of Egyptian history. A political and religious revolutionary, Akhenaten introduced Atenism by the fourth year of his reign, raising the previously obscure god Aten (sometimes spelled Aton) to the position of supreme deity, suppressing the worship of other deities, and attacking the power of the entrenched Amen-Ra priestly establishment.  A house altar depicting the Pharaoh Akhenaten and his family receiving life from the rays of the Aten sun disk, on display at the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin A new culture of art was introduced during this time that was more naturalistic and realistic. It was a departure from the stereotypical style that had predominated in Egyptian art for the previous 1700 years. Depictions of Akhenaten show exaggerated physical features. Styles of art that flourished during this short period are markedly different from other Egyptian art, bearing a variety of affectations, from elongated heads to protruding stomachs, exaggerated features, and as a contrast, the beauty of his queen Nefertiti. The period following Akhenaten's death is confused and poorly attested, but worship of the old gods was revived and the reign of Tutankhamun marks the certain re-emergence of the old traditions. He was a young child when he ascended to the throne, and undoubtedly it was his advisers who made decisions for him. His given name was Tutankhaten, but with the resurgence of Amun, he was re-named Tutankhamun. Tutankhamun died while he was still a teenager and was succeeded by Ay, who probably married Tutankhamun's widow to make his claim to the throne. When Ay died a few years later, Tutankhamun's former General Horemheb became ruler, and a new period of positive rule began. He set about securing internal stability and re-establishing the prestige that the country had before the reign of Akhenaten. When Horemheb died without an heir, he named his General Paramessu as his successor. Paramessu took the throne name Ramesses, and is considered the founder of the Nineteenth Dynasty. Ramesses I only reigned for a couple of years and was succeeded by his son Seti I. Seti I carried on the work of Horemheb in restoring power, control, and respect to Egypt. He also was responsible for creating the best known part of the temple complex at Abydos, his own mortuary temple. Arguably, Ancient Egypt's power as a nation-state peaked during the reign of Ramesses II ("the Great") of the nineteenth dynasty. He reigned for 67 years from the age of 18. He carried on his immediate predecessor's work and created many more splendid temples, such as that of Abu Simbel on the Nubian border. He sought to recover territories in the Levant that had been held by eighteenth dynasty Egypt. His campaigns of reconquest culminated in the Battle of Kadesh, where he led Egyptian armies against those of the Hittite king Muwatalli II, but was caught in history's first recorded military ambush. Ramesses II was famed for the huge number of children he sired by his numerous wives and concubines. The tomb he built for his sons, many of whom he outlived, in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be the largest funerary complex in Egypt. His immediate successors continued the military campaigns, although an increasingly troubled court complicated matters. Ramesses II was succeeded by his son, Merneptah, and then by Merenptah's son, Seti II. Seti II's throne seems to have been disputed by his half-brother, Amenmesse, who temporarily may have ruled from Thebes. The power of dynasty slowly receded and failed, leading to the reign of the last "great" pharaoh from the New Kingdom, Ramesses III, the son of Setnakhte who reigned three decades after the time of Ramesses II. In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea Peoples, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. He claimed that he incorporated them as subject peoples and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is evidence that they forced their way into Canaan. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region, such as Philistia, after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. He was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.[17] The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the Egypt's favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Deir el Medina could not be provisioned.[18] Following Ramesses III's death there was endless bickering among his heirs. Three of his sons would go on to assume power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI, and Ramesses VIII respectively. However, at this time Egypt also was increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest, and official corruption. The power of the last pharaoh of this dynasty, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the effective defacto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI's death, this was a period of turmoil known as Whm Mswt. Smendes eventually would found the twenty-first dynasty at Tanis. Third Intermediate Period Sphinx of the Nubian pharaoh Taharqa After the death of Ramesses XI, his successor Smendes ruled from the city of Tanis in the north, while the High Priests of Amun at Thebes had effective rule of the south of the country, whilst still nominally recognizing Smendes as king.[19] In fact, this division was less significant than it seems, since both priests and pharaohs came from the same family. Piankh, assumed control of Upper Egypt, ruling from Thebes, with the northern limit of his control ending at Al-Hibah. They were replaced without any apparent struggle by the Libyan kings of the twenty-second dynasty. Shoshenq I, the first king of the new dynasty, briefly re-unified the country, putting control of the Amun clergy under that of his own son. The scant and patchy nature of the written records from this period suggests that it was an unsettled time, leading eventually to a separate group of pharaohs who established their control over Upper Egypt (comprising the twenty-third dynasty) which ran concurrently with the latter part of the twenty-second dynasty. Under king Piye, the Nubian founder of twenty-fifth dynasty, the Nubians pushed north in an effort to crush his Libyan opponents ruling in the Delta. He managed to attain power as far as Memphis. His opponent Tefnakhte ultimately submitted to him, but he was allowed to remain in power in Lower Egypt and founded the short-lived twenty-fourth dynasty at Sais. Piye was succeeded first by his brother, Shabaka, and then by his two sons Shebitku and Taharqa. The international prestige of Egypt declined considerably by this time. The country's international allies had fallen under the Assyrian sphere of influence and, from about 700 BC the question became when, not if, there would be war between the two states. Taharqa's reign and that of his successor, Tanutamun, were filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians against whom there were numerous victories. Ultimately Thebes was occupied and Memphis sacked. Late PeriodFrom 664 BC Egypt was ruled by client kings established by the Assyrians, establishing the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. Psamtik I was the first to be recognized as the king of the whole of Egypt, and he brought increased stability to the country during a 54-year reign from the new capital of Sais. Four successive Saite kings continued guiding Egypt successfully and peacefully from 610-526 BC. By the end of this period a new power was growing in the Near East: Persia. The pharaoh Psamtik III had to face the might of Persia at Pelusium; he was defeated and briefly escaped to Memphis, but ultimately was captured and then executed at Susa, capital of the Persian king Cambyses, who assumed the formal title of Pharaoh, starting a period of Persian domination. Memphis and the Delta region became the target of many attacks from the Assyrians, until Psammetichus I managed to reunite Middle and Lower Egypt under his rule forming the Twenty-sixth dynasty. The last pharaoh of the Twenty-Sixth dynasty, Psammetichus III, was defeated by Cambyses II of Persia in the battle of Pelusium in the eastern Nile delta in 525 BC, Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. Thus began the first period of Persian rule over Egypt (also known as the Twenty-Seventh dynasty of Egypt), which ended around 402 BC. The Thirtieth Dynasty was established in 380 BC and lasted until 343 BC. This was the last native house to rule Egypt. The brief restoration of Persian rule is sometimes known as the Thirty-First Dynasty, which lasted for a brief period (343–332 BC). In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and then the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley. [edit] Ptolemaic dynasty Cleopatra VII adopted the ancient traditions and language of Egypt In 332 BC Alexander III of Macedon conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians. He was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. He visited Memphis, and went on pilgrimage to the oracle of Amun at the Oasis of Siwa. The oracle declared him to be the son of Amun. He conciliated the Egyptians by the respect which he showed for their religion, but he appointed Greeks to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital. The wealth of Egypt could now be harnessed for Alexander's conquest of the rest of the Persian Empire. Early in 331 BC he was ready to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. He left Cleomenes as the ruling nomarch to control Egypt in his absence. Alexander never returned to Egypt. Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC, a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Initially, Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and then as regent for both Philip III and Alexander's infant son Alexander IV of Macedon, who had not been born at the time of his father's death. Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander's closest companions, to be satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy ruled Egypt from 323 BC, nominally in the name of the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV. However, as Alexander the Great's empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as ruler in his own right. Ptolemy successfully defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC, and consolidated his position in Egypt and the surrounding areas during the Wars of the Diadochi (322 BC-301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy took the title of King. As Ptolemy I Soter ("Saviour"), he founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years. The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life.[20][21] Hellenistic culture thrived in Egypt well after the Muslim conquest. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome. Roman dominationAfter the defeat of Marc Antony and Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII in the Battle of Actium in 30 BC by Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus), Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire, encompassing most of modern-day Egypt except for the Sinai Peninsula, bordered by the provinces of Cyrenaica to the west and Arabia, Egypt would come to serve as a major producer of grain for the empire. The reign of Constantine also saw the founding of Constantinople as a new capital for the Roman Empire, and in the course of the fourth century the Empire was divided in two, with Egypt finding itself in the Eastern Empire with its capital at Constantinople. This meant that within a few years Latin, never well established in Egypt, disappeared, and Greek reasserted itself as the language of government. During the fifth and sixth centuries the Eastern Roman Empire gradually became the Byzantine Empire, a Christian, Greek-speaking state that had little in common with the old empire of Rome, which disappeared in the face of the Islamic invasions in the fifteenth century. Another consequence of the triumph of Christianity was the final oppression and demise of the pagan culture: with the disappearance of the Egyptian priests and priestesses who officiated at the temples, no-one could read the hieroglyphics of Pharaonic Egypt, and its temples were converted to churches or abandoned to the desert. The Eastern Empire became increasingly "oriental" in style as its links with the old Græco-Roman world faded. The Greek system of local government by citizens had now entirely disappeared. Offices, with new Byzantine names, were almost hereditary in the wealthy land-owning families. Alexandria, the second city of the empire, continued to be a centre of religious controversy and violence. Cyril, the patriarch of Alexandria, convinced the city's governor to expel the Jews from the city in 415 with the aid of the mob, in response to the Jews' nighttime massacre of many Christians. The murder of the philosopher Hypatia marked the final end of classical Hellenic culture in Egypt. Another schism in the Church produced a prolonged civil war and alienated Egypt from the Empire. Muslim conquestEgypt had been occupied just a decade before the conquest by the Persian Empire under Khosrau II (616 to 629 AD). An army of 4,000 Arabs led by Amr Ibn Al-Aas was sent by the Caliph Umar, successor to Muhammad, to spread Islamic rule to the west. These Arabs crossed into Egypt from Palestine in December 639, and advanced rapidly into the Nile Delta. The Imperial garrisons retreated into the walled towns, where they successfully held out for a year or more (although the Arabs were victorious at the Battle of Heliopolis in July 640.[22] But the Arabs sent for reinforcements, In April 641 they captured Alexandria. The Thebaid seems to have surrendered with scarcely any opposition. Most of the Egyptian Christians welcomed their new rulers: the accession of a new regime meant for them the end of the persecutions by the Byzantine state church. The Byzantines assembled a fleet with the aim of recapturing Egypt, and won back Alexandria in 645, but the Muslims retook the city in 646, completing the conquest | |

Egyptian hieroglyphics had been used by the Egyptians for thousands of years. However, a particularly bleak period of Egyptian history is the conquest of Egypt by Persia. The Egyptians were dominated by Persian intruders. The events that changed the nature of Egypt were not the Persian conquest but rather the war between Persia (the rulers of Egypt) and the united Greek city-states. Greece had originally been united by Philip of Macedon and then ruled effectively by Alexander the Great. Alexander defeated the Persian forces and then took his army to Egypt. There he was welcomed as a conquering hero by the Egyptians because he brought an end to Persian rule. He was made a god by the Egyptians as well as a pharaoh. He, however, had other campaigns to wage and took his army off to the Middle East and the Indus River Valley leaving a regent in charge of Egypt.

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, his empire was divided among his three most trusted and powerful generals. The throne of Egypt fell to Ptolemy I, the son of Lagus. Ptolemy took Alexander’s preserved body in a jar filled with honey back to Alexandria. Ptolemy ran Egypt like a business, strictly for profit. . He was welcomed by the Egyptians as part of Alexander the Great’s family. Ptolemy then became the pharaoh, Ptolemy I. By so doing, he set the name standard for the 32nd Dynasty which turned out to be the last of Egypt’s great dynasties. All of his male successors were called Ptolemy and all of his female successors were called Cleopatra.

As we move to the end of this Greek Dynasty, there was increasing involvement with the Roman Empire. The Roman civil war between Caesar and Pompeii indirectly involved Egypt. Pompeii lost this war and turned to Egypt for shelter and young Ptolemy (several generations below Ptolemy I) had him executed and delivered to Caesar. The young Ptolemy, thinking this would ingratiate him with Caesar was totally incorrect. His sister, Cleopatra, who was vying for the throne had other ways of ingratiating herself with Caesar - they had children together. Caesar was unfortunately assassinated while visiting Rome and his empire was divided up between General Marcus Antonious and his adopted son, Octavian. Marcus Antonious was better known as Marc Antony. Marc Antony took rulership of that part of the Empire that contained Egypt and that resulted in his inheriting Cleopatra. They, too, had children. His relationship with Octavian broke down and resulted in a war which Marc Antony lost. Antony was killed and Cleopatra committed suicide. Their male children were executed and their female children were probably married off to local princes. The Egyptian dynastic system was ended and a Roman Governorship was established.

During the Ptolemic dynasty, Egyptian and Greek languages were used simultaneously. During the Roman Governorship only Latin was used and occasionally Greek. Within a hundred years the Egyptian hieroglyphics were no longer used or understood by anyone and even the Roman authors of the time suggested that hieroglyphics was not even a language. In the truest sense this is now a dead language.

Ultimately the Roman Empire fell and the Middle Ages "came about". Nevertheless, there existed a constant contact between Europe and Egypt such that hieroglyphics were consistently known by the European elite. The reason for this is that medical practices of the Middle Ages resulted in the prescription of bitumen, ground up mummies as a cure for various kinds of diseases. Thus, there was a trade in whole mummies which resulted in examples of hieroglyphics coming into Europe throughout the Dark Ages.

As a result, there were some early attempts at translation of hieroglyphics. In 1633, a Jesuit priest named Anthanasius Kircher, whose specialities were the humanities, science, language and religion translated the word ‘autocrat’ or in Greek ‘autocratur’ into German and did so by substituting ideas for the images. His translation read "the originator of all moisture and all vegetation whose creative forces is brought into this kingdom by the holy mukta" (is this a ‘bureaucrat’?)

The history of the deciphering of the Egyptian hieroglyphics during the 16th and 17th centuries took small steps toward final interpretation. Some scholars thought that the hieroglyphics were the origin of other languages. Some believed that hieroglyphics spelled nothing at all. Yet others believed that the hieroglyphics were an indication of social stratification or social significance.

This speculation would have continued had not a political event interceded. The almost constant warfare between Britain and France resulted in  a major change in the understanding of hieroglyphics. The French under Napoleon Bonaparte decided that they could defeat the British by attacking Egypt and subsequently controlling the rich food supply from along the Nile.

a major change in the understanding of hieroglyphics. The French under Napoleon Bonaparte decided that they could defeat the British by attacking Egypt and subsequently controlling the rich food supply from along the Nile.

In August of 1798, 13 French ships landed near Alexandria at Aboukir Bay in Egypt and marched inland to fight the British near Cairo. The night before the battle, Napoleon exhorted his troops on by saying something like "Soldiers, from the tops of these pyramids, forty centuries are looking down at you." The French ground forces won the conflict but the British navy, under the command of Lord Horratio Nelson, defeated the French navy. Napoleon believed that he would be in Egypt for only a few months, but he and his men were stranded there for three years with no way to return home. Napoleon had brought with him between nearly 1000 civilians including 167 of whom were scientists, technicians, mathematicians and artists who studied the art, architecture, and culture of Egypt during their "extended vacation." From 1809-1828, they published a 19-volume work called Description of Egypt. Their observations, drawings and illustrations were circulated throughout Europe and created a tremendous interest in antiquities of Egypt.

The soldiers continued to "dig in" and they reconstructed forts as most soldiers had done during previous centuries by using building stones previously used by earlier peoples. In 1799, while extending a fortress near Rosetta, a small city near Alexandria, a young French officer named Pierre-Francois Bouchard found a block of black basalt stone. It measured three feet nine inches long, two feet four and half inches wide, and eleven inches thick and it contained three distinct bands of writing. The most incomplete was the top band containing hieroglyphics, the middle band was an Egyptian script called Demotic script (he did not know that), and the bottom was ancient Greek (he did recognize the bottom band). This stone was called the Rosetta Stone. He took the stone to the scholars and they realized that it was a royal decree that basically stated that it was to be written in the languages used in Egypt at the time. Scholars began to focus on the Demotic script, the middle band, because it was more complete and it looked more like letters than the pictures in the upper band that were hieroglyphics. It was essentially a shorthand hieroglyphics that had evolved from an earlier shorthand version of Egyptian called Heiratic script.

Material from Egypt was continuously coming into Europe. In order to display their status, the European gentry and nobility normally had some  Egyptian relics in their possession, perhaps an art object on a table or if one were quite rich, they might have an obelisk in the front yard of the estate. Material containing hieroglyphics continued to enter Europe at a reasonably accelerated rate.

Egyptian relics in their possession, perhaps an art object on a table or if one were quite rich, they might have an obelisk in the front yard of the estate. Material containing hieroglyphics continued to enter Europe at a reasonably accelerated rate.

The first to make any sense of the Demotic script on the Rosetta Stone was a French scholar named Silvestre deSacy. deSacy was an important and skilled French linguist. He identified the symbols which comprised the word ‘Ptolemy’ and ‘Alexander’ thus, establishing a relationship between the symbols and sounds. Johann Akerblad who history records as a Swedish diplomat, looked at the Rosetta Stone with an additional knowledge of Coptic. Coptic was the language used by the Coptic church of Egypt, an early Christian group who preserved the language which was used as early as the 4th century. Coptic was written with the Greek alphabet but utilizes seven additional symbols from the Demotic script. Akerblad’s knowledge of Coptic allowed him to identify the words for ‘love,’ ‘temple’ and ‘Greek’ thus, making it clear that the Demotic script was not only a phonetic script but it was also translatable.

The earliest translation of the Greek text on the Rosetta Stone into English was done by Reverend Stephen Weston in London in April 1802 before the Society of Antiquaries . About this time, both deSacy and Thomas Young, attempted to decipher the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone. Young was successful in determining that foreign names could not be represented by symbols because symbols are based upon the words used in a given language. Thus, foreign names had to be spelled phonetically. In hieroglyphics there are groups of symbols that are separated from other symbols. These encircled inscriptions are called cartouches. Thomas Young determined that the cartouches were proper names of people who were not Egyptian like the names of Ptolemy and Alexander which in Greek were Ptolemaios and Alexandrus. He successfully deciphered 5 cartouches. His publication on this matter was far reaching.

At this point there is involvement by a young French historian and linguist named Jean-Fracois Champollion. Champollion had mastered many Eastern languages. In 1807, Champollion went to study for two years with noted French linguist Francois Antoine-Isaac Silvestre deSacy. Later in his career, Champollion had compiled a Coptic dictionary and read Thomas Young in 1819. Looking at Young’s writing on the subject of hieroglyphics, he realized that what Young

Champollion had mastered many Eastern languages. In 1807, Champollion went to study for two years with noted French linguist Francois Antoine-Isaac Silvestre deSacy. Later in his career, Champollion had compiled a Coptic dictionary and read Thomas Young in 1819. Looking at Young’s writing on the subject of hieroglyphics, he realized that what Young  had actually proven was that all of hieroglyphics were phonetic, not just those hieroglyphics that were contained within the cartouches. Utilizing hieroglyphics from an estate at Kingston Lacey in Britain, Champollion correctly identified the names of Cleopatra and Alexandrus and verified Ptolemeus which had previously been identified by Young He published his results and continued his research. In 1822 new inscriptions from a temple at Abu Simbel on the Nile were introduced into Europe and Champollion had correctly identified the name of the pharaoh who had built the temple. That name was ‘Ramses.’ Utilizing his knowledge of Coptic he continued to successfully translate the hieroglyphics opening up an understanding of the Ancient Egyptians.

had actually proven was that all of hieroglyphics were phonetic, not just those hieroglyphics that were contained within the cartouches. Utilizing hieroglyphics from an estate at Kingston Lacey in Britain, Champollion correctly identified the names of Cleopatra and Alexandrus and verified Ptolemeus which had previously been identified by Young He published his results and continued his research. In 1822 new inscriptions from a temple at Abu Simbel on the Nile were introduced into Europe and Champollion had correctly identified the name of the pharaoh who had built the temple. That name was ‘Ramses.’ Utilizing his knowledge of Coptic he continued to successfully translate the hieroglyphics opening up an understanding of the Ancient Egyptians.

.

Blog Archive

-

►

2009

(10)

- ► 03/08 - 03/15 (4)

- ► 03/01 - 03/08 (6)

-

►

2008

(51)

- ► 03/30 - 04/06 (11)

- ► 03/02 - 03/09 (1)

- ► 02/24 - 03/02 (26)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (7)

- ► 01/27 - 02/03 (2)

- ► 01/13 - 01/20 (4)